Aila Hoss, 2020-21 Courage research fellow and Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Tulsa, talks about the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision McGirt v. Oklahoma and discusses how it takes courage to confront the racist legacies embedded in our laws.

Aila Hoss, 2020-21 Courage research fellow and Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Tulsa, talks about the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision McGirt v. Oklahoma and discusses how it takes courage to confront the racist legacies embedded in our laws.

As a 2020-21 fellow with the Oklahoma Center for Humanities, I’ve explored the idea of courage alongside faculty, staff, students, and other members of the TU community. Our discussion has often turned to the idea of challenging existing narratives – in science, philosophy, and law – as an exercise of courage. One pervasive narrative in federal Indian law is the idea that Tribal authority is a threat to state or local governments and their non-Tribal citizens.

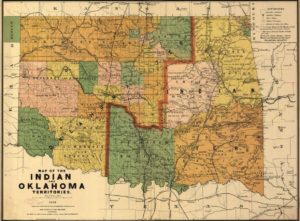

The recent U.S. Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma was a victory stewarded by the Muscogee Creek Nation and celebrated by all of Indian country. The decision reaffirmed the Tribe’s treaty reservation boundaries, boundaries longed infringed upon by state and local governments.

The recent U.S. Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma was a victory stewarded by the Muscogee Creek Nation and celebrated by all of Indian country. The decision reaffirmed the Tribe’s treaty reservation boundaries, boundaries longed infringed upon by state and local governments.

Oklahoma’s Attorney General, in response to well-founded criticisms of proposed legislation to limit the impact of the McGirt decision, called critics “sovereignty hobbyists,” deeming concerns about infringement of sovereignty theoretical. In its brief in the McGirt decision, Oklahoma argued that the state, not the Tribe, that had the “ultimate responsibility for seeking justice for Indian crime victims.” Sadly, such challenges to Tribal sovereignty are not new.

Courts have long relied on overt racism and white supremacy to justify infringement on Tribal sovereignty and Indigenous rights. Attorney and scholar Walter Echo-Hawk describes the ten worst Indian law cases in his book, In the Courts of the Conqueror, which explores the impact of these cases on a variety of areas including property rights, political status, and culture.

I offer an excerpt from just one case, although there are countless others, to demonstrate how pervasive racism is in our case law. In US v. Sandavol, the Supreme Court stated that “[t]he people of the pueblos . . . adher[e] to primitive modes of life, largely influenced by superstition and fetichism, and chiefly governed according to the crude customs inherited from their ancestors, they are essentially a simple, uninformed, and inferior people.” Modern day manifestations of these sentiments in mascots and media have been described as the “last acceptable racism.”

In our courtrooms today, racism against American Indians and Alaska Natives is packaged under legal arguments challenging Tribal sovereignty. Under the guise of federal Indian law, individuals, corporations, and governments regularly argue that Tribes do not and should not have the legal authority that is both inherent to them as sovereign nations and long recognized under the law. These arguments are bolstered by thinly-veiled, racist stereotypes that Tribes do not have the ability or interest to govern themselves. When the law embraces these stereotypes, Tribes lose legal authority essential to protecting their communities, lands, and cultures. Wallace Coffey and Rebecca Tsosie discuss the inextricable relationship between legal sovereignty and cultural sovereignty in, “Rethinking the Tribal Sovereignty Doctrine: Cultural Sovereignty and the Collective Future of Indian Nations.”

In our courtrooms today, racism against American Indians and Alaska Natives is packaged under legal arguments challenging Tribal sovereignty. Under the guise of federal Indian law, individuals, corporations, and governments regularly argue that Tribes do not and should not have the legal authority that is both inherent to them as sovereign nations and long recognized under the law. These arguments are bolstered by thinly-veiled, racist stereotypes that Tribes do not have the ability or interest to govern themselves. When the law embraces these stereotypes, Tribes lose legal authority essential to protecting their communities, lands, and cultures. Wallace Coffey and Rebecca Tsosie discuss the inextricable relationship between legal sovereignty and cultural sovereignty in, “Rethinking the Tribal Sovereignty Doctrine: Cultural Sovereignty and the Collective Future of Indian Nations.”

Many people and entities benefit financially, politically, and socially from undermining Tribal sovereignty and use this as an argument to challenge Tribal jurisdiction legally. This practice needs to stop. Financial, political, and social inconvenience should not be sufficient grounds to challenge the inherent rights of Tribal nations. Yet, such litigation is not only commonplace but also endorsed by courts that are persuaded by these arguments.

It takes courage to first confront and then change this racist legacy embedded in our laws, particularly from entities that historically challenge Tribal jurisdiction. It will require us to replace existing narratives with a new one that acknowledges the benefit of sovereignty to both Tribes and their neighbors. As a non-Native resident in of the Muscogee Creek Nation and citizen of Oklahoma, I hope the state of Oklahoma has the courage to support Tribal jurisdiction instead of challenge it.

Sources:

Image – Map of Oklahoma Indian Lands (Library of Congress – public access): https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4021e.ct000224/

Image – Supreme Court (Library of Congress – public access): https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2019/05/celebrate-law-day-with-new-research-guides-from-the-law-library/